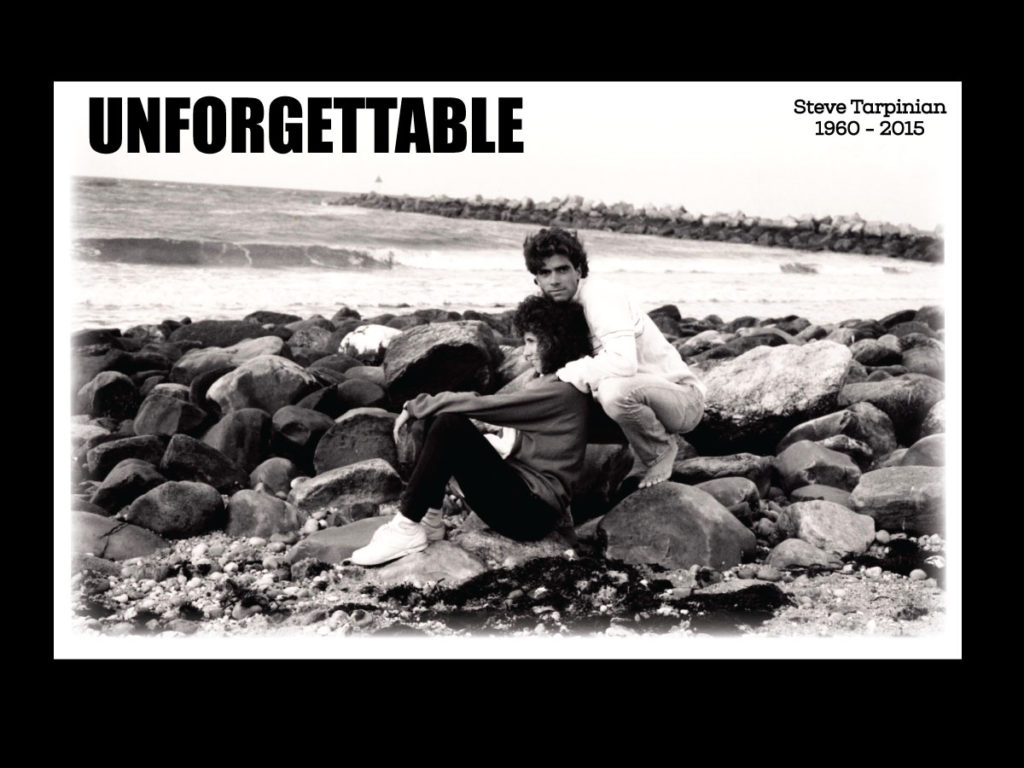

March 15, 2015 was the darkest day of my life. It was the day I lost my life partner, Steve Tarpinian, to suicide. We had been soul mates for over 33 years.

Have I made peace with his suicide?

If I separate the cause of Steve’s death from the tragedy of forever losing the love of my life, I can say yes.

I have come to terms with the fact there is nothing that I could have done that would have resulted in a different outcome. Steve’s mental anguish must have been so intense, so much so, that he lost sight of all the love surrounding him. He had already tried suicide once before and failed, so it seems out of his hopelessness, he was determined to try again. That is how insidious the disease of the mind is.

The first two years after losing Steve were filled with so many unanswered questions; ; “Why, he had so much going for him”, “What if I had said…” , “What if I didn’t say….”, “What could I have done differently?” , so there was no possible way for me to make peace with his suicide. At times these questions still haunt me, however, for the most part, I have accepted the fact that Steve made up his mind on his course of action and nothing anyone could have said or done was going to dissuade him. The suicide and mental illness collateral damage such as destroyed relationships, being blamed for his death, uncalled for vitriol aimed at me and judgments on how I grieved are fading from my memory. Hence, I believe I have finally made peace with his suicide.

Losing the love of my life is what I still struggle with even though I realize that this is now my new normal and that Steve and I will not grow old together and share the same pillow. There is a huge hole in my heart that can never be filled. Steve and I had a once in a lifetime relationship, filled with a deep respect and love for each other. When we love deeply, we grieve deeply. I am forever changed by Steve’s death. Yes, I still have days with meltdowns and not wanting to get out of bed in the morning, but, I am only human. My tears and sadness over the loss of Steve is now a part of who I am. As such, I have come to accept and embrace it.

My grief journey has taken me in directions that have helped me cope with my great loss. It is a daunting task and I must continuously remind myself to stay on track and not to fall back into the bottomless pit of despair. I realize that trying to make peace with losing Steve, regardless of the cause of his death, will be a lifelong commitment that will not come easily for me.

How do I cope with my loss?

Living in the moment and trying to pay it forward have helped me the most in moving forward in a life without Steve.

Within 7 months of Steve’s passing, I wrote and published his memoir; Slipped Away, a single minded task that did not permit me to wallow in self pity. Yes, it was draining, but, I was able to re-live many happy moments in my life with Steve. I wanted Slipped Away to be more a celebration of Steve’s life and how he positively impacted so many people rather than a book about suicide. The focus it took for me to complete the book truly allowed me to live in the moment.

Since publishing, I now do book talks, write blogs and use social media in an effort to inspire conversation about suicide and mental health issues. These topics, even to this day, are still stigmatized and most people are embarrassed to talk about these issues and would prefer to stick their heads in the sand. As a suicide survivor, I have experienced this first hand.

In an attempt to try and have something good come out of such a tragic loss, I wanted the telling of Steve’s story to allow him to continue helping people even though he is no longer with us. The proceeds of Slipped Away are donated to Project9line.org; a non-profit organization of veterans helping other veterans deal with depression and PTSD that provides outlets for them in the arts (writing, music, comedy etc.). It was through Project9line that I was introduced to AirborneTriTeam.org (ATT). ATT’s mission is to promote teamwork and endurance sports to help veterans “… better their life style, change their attitude towards life and give them a purpose”. There was a great synergy with myself and ATT since Steve was an Ironman triathlete many times over and the company Steve built was responsible for the foundation of the sport of triathlon on Long Island. Supporting the veterans of ATT in their mission gives me a sense of purpose.

Steve was not a veteran, however, even though the paths that lead our veterans to suicide are different than Steve’s, they shared the similar pain of hopelessness and mental anguish. The end results of suicide are the same, the tragic, sudden loss of a precious life and the loved ones that are left behind, feeling the terrible heartbreak of loss, with so many unanswered questions, wondering if they could have done something different to help their loved one.

Never in my life I would have thought I would be affected by the suicide of a loved one, let alone trying to make peace with suicide. The time has come for me to accept my reality and as a suicide survivor, I can now say I have made peace with suicide.

Jean Mellano retired in 2010 from a 37-year career in the Information Technology industry. After so many years in the computer industry using the analytical side of her brain, she decided the time was right to exercise the more visual and perceptual side of her brain. Graphic design was a natural next step. Jean began to do the creative work for the event business of her 33+ year soul mate, Steve Tarpinian, designing event logos and promotional print work.

When Steve took his own life on March 15, 2015, her world changed dramatically and her life was turned upside down. Jean began to take solace in writing about Steve and found purpose in trying to bring more awareness to mental health by telling Steve’s story and published his memoir, Slipped Away.

In addition to her goals of keeping Steve’s legacy alive and inspiring conversation about mental illness and suicide, she is donating the majority of the profits from Slipped Away to a non- profit organization that is focused on supporting veterans suffering from PTSD and depression.