To the world

you might just be one person,

but to one person

you are the world.

—No Attribution

Frank Ostaseski tells this story:

Frank Ostaseski tells this story:

“When my son Gabe was about to be born, I wanted to understand how to bring his soul into the world. So I signed up for a workshop with Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, the renowned psychiatrist from Switzerland who was best known for her groundbreaking work on death and dying. She had helped many leave this life; I figured she might teach me how to invite my son into his.

Elisabeth was fascinated with the idea and took me under her wing. She invited me to attend more programs over the years, although she didn’t give me much instruction. I’d sit quietly in the back of the room and learn by watching the way she worked with people who were facing death or grieving tragic losses. This fundamentally shaped the way I later accompanied people in hospice care.

Elisabeth was skillful, intuitive, and often opinionated, but above all, she demonstrated how to love those she served, without reservation or attachment. Sometimes the anguish in the room was so overwhelming that I would meditate in order to calm myself or do compassion practices, Imagining that I could transform the pain I was witnessing.

One rainy night after a particularly difficult day, I was so shaken as I walked back to my room that I collapsed to my knees in a mud puddle and started to weep. My attempts at taking away the participants’ heartache were just a self-defense strategy, a way of trying to protect myself from suffering.

Just then, Elizabeth came along and picked me up. She brought me back to her room for a coffee and a cigarette. ‘You have to open yourself up and let the pain move through you,’ Elizabeth said. ‘It’s not yours to hold.’ Without this lesson, I don’t think I could have stayed present, in a healthy way, with the suffering I would witness in the decades to come.”

From the Introduction: The Transformative Power of Death

Page 6 – 7

The Five Invitations: Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully

by Frank Ostaseski

If I had to tell someone who is a survivor of a loved one who committed suicide, one piece of advice I would say is experience the wound; experience the shock, the trauma, and let it wash over you knowing it won’t destroy you, and trust that in time, like all wounds, you heal, and feel peace that your loved one is no longer suffering.

These and other sage words of wisdom, advice and counsel are included in Making Peace with Suicide: A Book of Hope, Understanding and Comfort.

Suicide is not an easy conversation. Period. It is weighted with the feelings of real or perceived judgment and taboo.

Survivors search and seek for answers and clues about the thinking and feeling behind their loved one’s choice to irrevocably end it all. How could this be? Why did this happen? What caused this? What was the tipping point? Didn’t you love me and the kids enough to stay? What could I have done differently? Why aren’t you here? You know it was their choice, but you still feel responsible — in a conflicted, connected way — and wonder if you could have done anything to change the outcome.

For the survivor, suicide is unbelievable and surreal. It is a game changer. Your life is permanently altered. It is the day time stands still. It is the day you stop taking a full breath. It is, alas, the day people can avoid you; talk about you; and, even, blame you.

Continue reading here:

http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/adele-mcdowell/grieving-suicide_b_8615376.html

Suicide is desolate. It is weighted with shame and secrecy, criticism and judgment. Too often there is little compassion for those who have chosen to end their lives. And compassion or support for the survivors of suicide is often embarrassed and spare.

Suicide is desolate. It is weighted with shame and secrecy, criticism and judgment. Too often there is little compassion for those who have chosen to end their lives. And compassion or support for the survivors of suicide is often embarrassed and spare.

Surviving loved ones are traumatized as they hold the remains of a shattered life in their hands. They are full of questions, recriminations, and their own mixed emotions. Why did this happen? Why didn’t I see this coming? Could I have done something more? A suicidal death expresses a failure that leaves unanswered questions and complicated grief in its wake.

But it is possible to find a way to go on and to heal.

This seven-step method is a shorthand template to help people trying to find their way out of the rabbit hole of devastation.

1. Tell your story

Stories help us see the fuller picture and understand situations from a broader perspective. Your task is to tell your story in its entirety–the good, the bad, and the scary. In doing this, you give yourself permission to air what has been stuck within you. To get started, ask yourself questions such as: “What was the nature of your relationship?” and “What transpired over time?” Ideally, tell your story aloud to a trusted person who will agree not to respond or question in any way, but simply bear witness. Or, write your story and read it aloud. Light candles or sit beside a stream. Make this a sacred moment.

2. Own your part

Allow yourself to get very clear about the reality of the situation with your lost loved one. Take responsibility for your choices, or own your part in the relationship, and forgive yourself or any others you harbor anger toward. Know that forgiveness is about acceptance and not necessarily agreement or approval. We are all human and we all make mistakes; the important point is to learn from them. Find gratitude in the new understanding and let go with a light heart.

3. Debrief the dark moments

When we have been through a crisis, we need to give voice to our experiences. Identify your moments of darkness, as well as where you found inner strength. Pull out and examine the emotional details in order to move forward in your recovery.

4. Call back your spirit

We humans tend to hold on; we struggle with change and conflict. But over time, the incremental wear and tear takes its toll. We end up feeling weighted down with unresolved issues. Examine your feelings and ask yourself “What is unresolved?” Your goal is to release those energy-sucking thoughts and emotions, and decide how you will honor yourself going forward in a life-giving way. Calling back the spirit is not easy. It may take time and practice, and need repeated attention when facing new challenges. Find your individual ritual or thought process that re-empowers you to make peace, and stand in its fullness.

5. What are the lessons?

The life-altering experience of suicide creates lessons that can be windows to self-discovery. By recognizing what you now understand that you didn’t before–about yourself or a loved one–new perspectives and insights present themselves that place the experience into the broader whole.

6. Connect with your loved one

Use meditation to reconnect to the love you still share with the person you lost. Take 20-30 minutes to sit quietly with your hand on your heart, and with your breathing, send light and love to your lost loved one. Think of facing your loved one or sensing his or her presence. Drop any expectations, but just be present in a loving way. Another way to connect is through signs and symbols, particularly those observed in nature. Be aware of your loved one’s presence when you see a rainbow, or a hawk, or a particular flower. Think of these as messages meant for you.

7. Make a commitment to peace

Having worked through the previous six steps, honor your process of making peace with suicide in a way that provides a reminder of what was and what is now. Whichever way you choose to commemorate your experience–it can be writing a pledge to yourself, creating a visual reminder, or finding a symbol that stands for your journey–let it stand for your personal commitment to choosing peace over chaos and internal war. Allow your heart to guide you. This process makes your commitment tangible.

If I were to have a gravestone, preferably under a beautiful tree that flowers or, at least near a Chinese restaurant, I would want the gravestone to be etched with these words: I CAN STILL SEE YOU.

If I were to have a gravestone, preferably under a beautiful tree that flowers or, at least near a Chinese restaurant, I would want the gravestone to be etched with these words: I CAN STILL SEE YOU.

Of course, this makes me laugh. It has for days as I have been entertaining myself with this very thought. My overactive imagination conjures up this scene where you visit me at my gravesite and I see you and envision that we converse energetically. At first, you are surprised and somewhat dumbfounded, but I know so much about our history that ultimately you are convinced that a) this is real or b) you are having a lucid dream or c) you are playing make-believe and it’s kind of fun.

You see, I believe that our souls are eternal and our bodies are a bit like complicated robes that we shed upon death. The brain goes dark, but the consciousness lives.

For the past few weeks I have being seeing faces again. Yes, again. When I started writing Making Peace with Suicide, I would see faces in the leaves of a tree outside my window, on the tiles of my shower, and framed in groups on my carpet. Most recently, I have had visitors around my bed in the middle of the night. My feeling is that they are looking for relief by way of connection or, possibly, understanding.

When I ask what they want, I hear, “We want to be heard.” Ok, let’s proceed. This is the gist and sense of what I have heard:

• Some loved ones who have died by suicide have expressed regret that they left such heartache and turmoil. They did not want to cause you pain; they simply wanted to end their pain.

• For some of the younger ones who have left by suicide, there is surprise and, even, regret that they are no longer here on earth. Their choice was impulsive and, often, influenced by drugs and alcohol.

• There are some who are wildly relieved to be off this mortal coil. They were ready to go. They feel complete and satisfied with nary a doubt or regret.

• And there are some who orchestrated (on a soul level) their passing and they are doing huge works of service on our behalf from the Other Side.

Our souls have unique contracts and trajectories of growth and development. Life – and death – are not always what they seem at first glance.

So, imagine, if you will, that your deceased loved one can still see you and be there with you. And imagine that your loved one is holding you close as you take your next steps on your healing path.

It’s a lovely thought, isn’t it? And, some of us, believe that it is true.

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to visit sunny, palm-treed southern California, where it kisses the blue, blue of the Pacific Ocean. It is a beautiful part of the world. The purpose of my visit was to present my new work Making Peace with Suicide at The 2012 Compassionate Friends (TCF) annual national and international conference.

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to visit sunny, palm-treed southern California, where it kisses the blue, blue of the Pacific Ocean. It is a beautiful part of the world. The purpose of my visit was to present my new work Making Peace with Suicide at The 2012 Compassionate Friends (TCF) annual national and international conference.

The Compassionate Friends is a self-help group for parents who have lost a child at any age; they, also, offer support to grieving grandparents and siblings. Illness, murder, addiction, suicide, manslaughter, drunk drivers, freak accidents, still-born deaths — you name it — these folks have walked through that fire. It is unimaginably heartbreaking. And, yet, they gather and laugh and cry and help one another breathe again.

The hotel was entirely filled with conference attendees and the hotel next door held all of the over flow. I heard there were anywhere from 1300-1800 attendees. They came as families, individuals, couples, and friends.

Even though I have experienced grief first-hand, I have not lost a child, and, so, I felt a bit like a stranger in a strange land. This was new terrain.

While in the elevator, a lovely woman named Kathy made eye contact and we began a conversation as we exited the elevator and headed to one of the sessions. Kathy told me that since the death of her son, she has lost all of her friends and that is why she came to TCF conference.

Initially, I was shocked and horrified, but as I talked to other parents they told me similar stories. It’s not that people are bad, they would all say. They just don’t know how to handle the weight of the grief. They don’t know what to say, how to say it, or they nervously make inappropriate or inane comments.

For example, one father told me that as he walked out of his son’s memorial service and settled into his car, his brother-in-law talked non-stop about his own son and his current career concerns. The bereft dad looked at his unaware brother-in-law and responded, “At least, you have a son.”

The parents acknowledged that many of their friends and loved ones were uncomfortable talking about death. Some told me that they felt it was too much of a burden for many of their friends. And, still, many of these parents want to talk about their sons and daughters; they never tire of the subject and the conversation keeps them alive in their hearts. These parents have come to recognize the squirm in others who do not know how to respond.

The Compassionate Friends has local chapters world-wide. Parents find other parents who know first-hand the sucker punch to the gut of losing a child and the crazy-making grief that ensues.

One week, at Kathy’s local group in her hometown, five new people attended their first Compassionate Friends’ meeting. That week, each person had lost a child to suicide. It was an emotionally intense meeting. Kathy said that she and another mom connected. In the weeks that followed, the new mom reached out to Kathy for support and guidance. Kathy said that was a turning point for her – in saying yes to the other mom-in-need, Kathy decided to live. In that helping, Kathy found a reason to keep going.

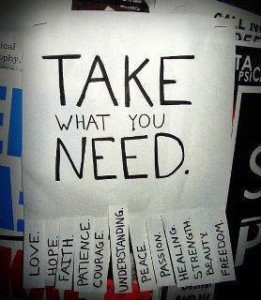

We, human beings, are so much more than we realize. We are resilient and tender. Our feelings can run deep and wide. We can be vulnerable, strong, understanding and, above all, compassionate. There are times when we all need a little help from our friends.