This was a great interview. Thank you, Susan! I so appreciate your sensitivity and understanding on this tough topic.

This was a great interview. Thank you, Susan! I so appreciate your sensitivity and understanding on this tough topic.

Source: The Pain of Suicide: Preventing and Coping With Tragedy

This was a great interview. Thank you, Susan! I so appreciate your sensitivity and understanding on this tough topic.

This was a great interview. Thank you, Susan! I so appreciate your sensitivity and understanding on this tough topic.

Source: The Pain of Suicide: Preventing and Coping With Tragedy

When a loved one dies by suicide, overwhelming emotions can leave you reeling. Your grief might be heart wrenching. At the same time, you might be consumed by guilt — wondering if you could have done something to prevent your loved one’s death.

When a loved one dies by suicide, overwhelming emotions can leave you reeling. Your grief might be heart wrenching. At the same time, you might be consumed by guilt — wondering if you could have done something to prevent your loved one’s death.

As you face life after a loved one’s suicide, remember that you don’t have to go through it alone.

Brace for powerful emotions

A loved one’s suicide can trigger intense emotions.

You might continue to experience intense reactions during the weeks and months after your loved one’s suicide — including nightmares, flashbacks, difficulty concentrating, social withdrawal and loss of interest in usual activities — especially if you witnessed or discovered the suicide.

Many people have trouble discussing suicide, and might not reach out to you. This could leave you feeling isolated or abandoned if the support you expected to receive just isn’t there.

Additionally, some religions limit the rituals available to people who’ve died by suicide, which could also leave you feeling alone. You might also feel deprived of some of the usual tools you depended on in the past to help you cope.

The aftermath of a loved one’s suicide can be physically and emotionally exhausting. As you work through your grief, be careful to protect your own well-being.

If you experience intense or unrelenting anguish or physical problems, ask your doctor or mental health provider for help. Seeking professional help is especially important if you think you might be depressed or you have recurring thoughts of suicide. Unresolved grief can turn into complicated grief, where painful emotions are so long lasting and severe that you have trouble resuming your own life.

Depending on the circumstances, you might benefit from individual or family therapy — either to get you through the worst of the crisis or to help you adjust to life after suicide. Short-term medication can be helpful in some cases, too.

In the aftermath of a loved one’s suicide, you might feel like you can’t go on or that you’ll never enjoy life again.

In truth, you might always wonder why it happened — and reminders might trigger painful feelings even years later. Eventually, however, the raw intensity of your grief will fade. The tragedy of the suicide won’t dominate your days and nights.

Understanding the complicated legacy of suicide and how to cope with palpable grief can help you find peace and healing, while still honoring the memory of your loved one.

This article was written by the Mayo Clinic Staff.

This is Janie Brown’s beautifully compassionate and loving response to a friend’s struggle with mental illness and later, suicide. The original piece was featured on Krista Tibbett’s “On Being” blog, where Janie Brown was a guest contributor.

This is Janie Brown’s beautifully compassionate and loving response to a friend’s struggle with mental illness and later, suicide. The original piece was featured on Krista Tibbett’s “On Being” blog, where Janie Brown was a guest contributor.

Dearest you,

The phone message you left yesterday from an unidentified B&B somewhere on Vancouver Island said I would know by morning whether you had chosen to live or die. You said the pills were lined up, counted, on the dresser.

A month before when you were unraveling again, you asked us, your closest friends, what we thought about you choosing to end your life, and we all said the same thing: “You must be tired of it all after so many cycles of mental illness in your sixty-two years, but with medication and therapy you always get better.” We always had a “but,” a reason we wanted you to keep choosing life. We hadn’t accepted you had a terminal illness then, a terminal mental illness. If you had advanced cancer, we might not have tried so hard to encourage you to keep going, if you hadn’t wanted to.

Today, I know what I want. I want you to live so we’ll carry on being friends, as we have for twenty-five years. I want you to continue to sharpen my knives and bring me organic beef for the freezer when you come to town. I want to call and hear your business voice on the answering machine. I want to look across the room and feel your heart as wide as the universe as you play your ukulele with abandon, your voice belting out Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry.” I want to feel your love for me, your deep caring that my life matters to you.

Most of all I want you to be happy.

But I know it’s not about what I want.

If you choose to live maybe you’ll find a sweet little home here in Vancouver just around the corner from us, and we can have dinners, and music nights, walks, and late-night conversations. We can work together, cook together, and drink good wine together. Ultimately, we would see each other through and out of this life.

If you choose to die tonight, I will carry no judgment, just a huge ache in my heart of missing you. You have lived a beautiful life, and a tough one. You have had to encompass more internally than anyone I have ever known, and I have nothing but admiration and respect for the way you have conducted your life. You are a good person. You have tried. You have succeeded on so many levels. I hope that if you choose to leave, you will truly know what a life of devoted service you’ve lived, and that you have loved, and that you have been loved in return.

Whether you choose to live or die today, I will always love you.

She chose to live that night. She said she was too scared to be alone, as she died.

A week later her psychiatrist and her closest friends encouraged her to go to a hospital where she would be kept safe from harming herself, and hopefully receive the treatment she needed to heal.

Even though she persuaded the occupational therapist to take her grocery shopping so she could make mulligatawny soup for the other in-patients (being a nutritionist, she worried the hospital food wouldn’t help them to get well); even though we snuck her out to a restaurant for a big salad, and a hearty glass of Cabernet Sauvignon against hospital regulations.

Even though we took a guitar and songbooks to the common room of the acute psychiatric unit, and sang together, and doors opened and patients peeked out, slowly sidling up to join the sing-a-long until an anxious nurse shut us down for fear of over-stimulating the patients.

Even though she did her best to maintain her dignity as her body survived the cycle of acute illness — her soul withered, slowly and quietly, over those months committed to a psychiatric unit.

Six months after she returned home, she told me she was unraveling again. She didn’t ask her friends what she should do, or tell them what she intended to do. One year ago this month, she didn’t wait until she was too ill to make the choice to die.

The day someone you love chooses to die must always feel too soon. September 5, 2014 was too soon for me, but I know it was likely not a moment too soon for my beloved friend. That day ended a lifetime of living with the enormous challenge of mental illness, a lifetime of immense loving and whole-hearted living, and a lifetime that impacted me more than I can possibly comprehend yet.

Janie Brown is the executive director of the Callanish Society, a nonprofit organization she co-founded in 1995 for people who are irrevocably changed by cancer, and who want to heal, whether it be into life, or death. An oncology nurse and therapist for almost thirty years, Janie explores her ideas through stories on her blog www.lifeindeath.org and is working on her first book.

Suicide is desolate. It is weighted with shame and secrecy, criticism and judgment. Too often there is little compassion for those who have chosen to end their lives. And compassion or support for the survivors of suicide is often embarrassed and spare.

Suicide is desolate. It is weighted with shame and secrecy, criticism and judgment. Too often there is little compassion for those who have chosen to end their lives. And compassion or support for the survivors of suicide is often embarrassed and spare.

Surviving loved ones are traumatized as they hold the remains of a shattered life in their hands. They are full of questions, recriminations, and their own mixed emotions. Why did this happen? Why didn’t I see this coming? Could I have done something more? A suicidal death expresses a failure that leaves unanswered questions and complicated grief in its wake.

But it is possible to find a way to go on and to heal.

This seven-step method is a shorthand template to help people trying to find their way out of the rabbit hole of devastation.

1. Tell your story

Stories help us see the fuller picture and understand situations from a broader perspective. Your task is to tell your story in its entirety–the good, the bad, and the scary. In doing this, you give yourself permission to air what has been stuck within you. To get started, ask yourself questions such as: “What was the nature of your relationship?” and “What transpired over time?” Ideally, tell your story aloud to a trusted person who will agree not to respond or question in any way, but simply bear witness. Or, write your story and read it aloud. Light candles or sit beside a stream. Make this a sacred moment.

2. Own your part

Allow yourself to get very clear about the reality of the situation with your lost loved one. Take responsibility for your choices, or own your part in the relationship, and forgive yourself or any others you harbor anger toward. Know that forgiveness is about acceptance and not necessarily agreement or approval. We are all human and we all make mistakes; the important point is to learn from them. Find gratitude in the new understanding and let go with a light heart.

3. Debrief the dark moments

When we have been through a crisis, we need to give voice to our experiences. Identify your moments of darkness, as well as where you found inner strength. Pull out and examine the emotional details in order to move forward in your recovery.

4. Call back your spirit

We humans tend to hold on; we struggle with change and conflict. But over time, the incremental wear and tear takes its toll. We end up feeling weighted down with unresolved issues. Examine your feelings and ask yourself “What is unresolved?” Your goal is to release those energy-sucking thoughts and emotions, and decide how you will honor yourself going forward in a life-giving way. Calling back the spirit is not easy. It may take time and practice, and need repeated attention when facing new challenges. Find your individual ritual or thought process that re-empowers you to make peace, and stand in its fullness.

5. What are the lessons?

The life-altering experience of suicide creates lessons that can be windows to self-discovery. By recognizing what you now understand that you didn’t before–about yourself or a loved one–new perspectives and insights present themselves that place the experience into the broader whole.

6. Connect with your loved one

Use meditation to reconnect to the love you still share with the person you lost. Take 20-30 minutes to sit quietly with your hand on your heart, and with your breathing, send light and love to your lost loved one. Think of facing your loved one or sensing his or her presence. Drop any expectations, but just be present in a loving way. Another way to connect is through signs and symbols, particularly those observed in nature. Be aware of your loved one’s presence when you see a rainbow, or a hawk, or a particular flower. Think of these as messages meant for you.

7. Make a commitment to peace

Having worked through the previous six steps, honor your process of making peace with suicide in a way that provides a reminder of what was and what is now. Whichever way you choose to commemorate your experience–it can be writing a pledge to yourself, creating a visual reminder, or finding a symbol that stands for your journey–let it stand for your personal commitment to choosing peace over chaos and internal war. Allow your heart to guide you. This process makes your commitment tangible.

Death is not easy on a regular basis, but death becomes tainted and shame-faced when described as a suicide. It’s hard to be left under such messy circumstances. You feel that somehow you failed to do your part. It feels as if the world sits in judgment, which only underscores the wracking guilt that hammers at you incessantly. You feel so responsible. You think you could have done something differently – made a move or said different words that might have tipped the balance in favor of life.

And you are angry, angry with a capital A, and, then, guilty because you are so angry. You loved them. You cared. Wasn’t your love enough? Did they think about you? How could they?

To read more, please click this link for the full article on The Huffington Post.

http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/adele-mcdowell/understanding-suicide-grief_b_7950622.html

Remember the theme song from the show M*A*S*H, “Suicide is painless?” From the surviving loved one’s viewpoint, nothing could be more wrong. Dealing with suicidal grief means overcoming enormous, overwhelming loss. It is, indeed, a hero’s journey.

Remember the theme song from the show M*A*S*H, “Suicide is painless?” From the surviving loved one’s viewpoint, nothing could be more wrong. Dealing with suicidal grief means overcoming enormous, overwhelming loss. It is, indeed, a hero’s journey.

A loved one’s suicide marks the day you stopped taking a full breath; the day you were left holding your broken heart in your hands and, unfortunately, the day people started avoiding, or, even, blaming you. You are left in a wake of surging emotions and self-doubt. The taint and taboo, the rage and despair, the guilt and regret are–in some brutal way–yours to sort out.

Due to proprietary agreements, I cannot feature the whole article here, but if you click this link to MariaShriver.com, you will find the remainder of the piece. I hope you find if of value. Many blessings to those of you walking this deeply challenging path.

Once upon a time, a woman, let’s call her Shirley, lost her husband to the ravages of cancer. It had been a long and arduous battle. Shirley was completely depleted on every level.

After the funeral service, everyone returned to the house. The coffee pot was plugged in; neighbors brought in food. Shirley excused herself from the din of family and friends and retreated to her bedroom, whereupon she fell into their king-size marital bed. She was utterly devastated and was totally lost without her husband, Charlie.

Then, a remarkable thing happened: Shirley felt Charlie hold her and comfort her as she lay cocooned in her grief. She wondered if she was simply imagining the very thing she wanted most in the world.

Fast forward a good six months. Shirley has now sold their home and moved into a small apartment. After the movers had finished their deliveries, Shirley walked aimlessly about and surveyed the disarray. Her once-familiar furniture seemed very out of place in the plain-vanilla box of what was to be her new home, her new home without the man she called the love of her life.

Shirley was overwhelmed and, as she was wont to do, Shirley, once again, took to her bed. And as you might guess, Charlie appeared again. He stood in the doorway and reassured her. Shirley told me that Charlie appeared about once a month for a number of months. Each and every time, Charlie stood in the doorway, leaning into the jamb in his own inimitable way. On his last visit, Charlie told Shirley that this was going to be his last visit as he knew she would now be okay.

Shirley asked me if I thought she was crazy. My answer was no, I believed that her Charlie was there to hold her and help her through her debilitating grief. I was happy for Shirley. She had had the comfort and reassurance of the connection; she had received, to my way of thinking, both a healing and a blessing—and it came from her husband on the “other side.”

From my perspective, the other side is thrumming with activity. I believe that those that have gone before us are cheering us forward towards a soulful, happy and joyous life. I believe that we are less alone than we imagine. Not only do we hold the memories in our minds, but we also hold the memories in our cell tissue and our hearts.

Death does not have to end a relationship. It can continue, albeit in new form, such as dreams, where, perhaps, you are given an answer to a question or affirmation for the next right step or, simply, a loving connection that fills your empty heart.

There can be the waft of a familiar scent, such as perfume, pipe smoke, roses or, even, alcohol that tells you your loved one is nearby.

There can be personal symbology as well. I know one man who feels affirmed by and connected with his deceased father every time he sees a blue heron—and in an area where blue herons are not known to populate. There is another woman who recognizes her deceased mother by the yellow butterflies that come to rest on her arm and hair for a good 20-30 minutes at a time.

There are the odd mechanical happenings, such as the woman whose deceased mother regularly turns on the radio to let her daughter know that they are still connected. Or, for another woman, there is the broken mantle clock that chimes every year on the date of her husband’s death.

The messages can come in all shapes and sizes. There is no one right way. It can be looking down and seeing a heart in midtown Manhattan and knowing, without a doubt, that it is a message from your mom. It can be meeting someone who says something that resonates within your heart and you know that person is the messenger for you.

It’s a matter of openness. It’s a matter of resonance. Are you open to the possibility? And, whatever is presented or unfolded, does it resonate within you?

I remember working with a 16 year-old girl; let’s call her Cassie, who was grieving the loss of her youngest brother in a family car accident. Early one Monday morning, their minivan had been hit hard — hard enough to flip over. Cassie recalls that at the time of the accident she was wearing a black-and-white summer skirt. When the minivan stopped rolling, Cassie noticed that her skirt was becoming red, and she, then, realized, with shock and horror, that her brother was crushed beneath her.

Cassie felt tremendous guilt that she was alive and that her brother had perished in the accident.

In one of our last sessions together, with Cassie’s permission and some prior prep work, I invoked the presence of her brother and asked for a message to help Cassie heal and assuage her suffocating guilt. Admittedly, Cassie was a bit suspect of this part of our work, but her curiosity outweighed her reservations.

Cassie was stretched out the couch, and I was seated in a chair placed near Cassie’s head. Cassie listens, with little or no reaction, as I relay messages from her brother. I, then, tell Cassie that I sense her brother is doing cartwheels down her body. Cassie begins to sob; she had felt the cartwheel movements before I even uttered the words.

For Cassie, this was physical proof of a connection with her brother, and served as a first step in her healing. And even better, Cassie later told me that her little brother was infamous in the family for his pride in his ability to do cartwheels. Clearly, her deceased little brother knew how to meaningfully connect with his big sister.

Children hold the faint memory of their soul time before birth and are less jaded about the possibility of the unknown. Some children see their guardian angels; others have imaginary friends. I wonder if some of these imaginary pals are more than a grand imagination, but spiritual allies at the ready.

This leads me to one more story.

There was a young boy, let’s call him Bobby, who was having Sunday dinner at his grandparent’s house. The dinner table was full; there were Bobby’s parents, his older brother and grandmother. His grandfather, who was at the end stages of cancer, was in bed; he was too weak and too ill to be part of this Sunday tradition.

Bobby raced through his meal, and, when finished, asked if he could be excused and rejoin his grandfather in the front bedroom. His parents gave their permission, and Bobby happily skipped off to be with his granddad.

A short while later, Bobby is yelling for his family to come quickly. Everyone bolts from the table and heads pell-mell to the grandfather’s bedroom. The adults check to see that the grandfather is resting comfortably and still breathing, and he is. Bobby, on the other hand, is wild-eyed and pointing to the end of the bed.

At the end of the bed, Bobby has seen a red-haired young boy, about his age, beckoning to his grandfather. Bobby wants to know who the red-haired boy is. His parents look blank, shrug their shoulders and shake their heads; they have no idea, nor do they see a red-haired boy. His grandmother, however, knows exactly who the red-haired boy is; he is the grandfather’s brother who died as a young boy in a boating accident.

Bobby’s mother came to me and asked if I thought Bobby’s vision was real. I said yes, and explained that it is not unusual for loved ones to ease the transition of their relatives. They offer familiarity and comfort in making the shift from human body to soul being.

For those left on the earth plane, the loss of a loved one can feel like cruel and unusual punishment. It is hard to absorb, much less accept, the permanency of the loss. We grieve for the dead, but, in reality, we are grieving the pain of the loss of connection with our loved one.

May I suggest that there might be more than merely the physical plane?

May I suggest that there might be deceased loved ones applauding your efforts regularly?

May I suggest that if you were to widen your perspective and expand your perceptions that there might be a few messages within your reach?

You know the feeling of love and connection; perhaps, it is closer than you think.

Every experience brings us wisdom. This is what Native Americans call “medicine,” also known as our personal power.

Every experience brings us wisdom. This is what Native Americans call “medicine,” also known as our personal power.

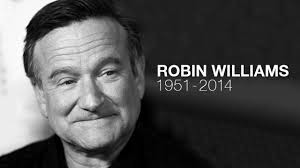

The shocking loss of Robin Williams on August 11, 2014 has had a profound impact on opening the door and bringing suicide out of the closet. Not only did Robin expand us with comic genius and acting during his lifetime, he opened our our hearts and stretched our minds with his death as well.

The Huffington Post (Canada) featured my article which identifies the lessons we have learned following his suicide. I invite you to click the link to read the article in full.

http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/adele-mcdowell/robin-williams-suicide_b_7850898.html

This is my favorite healing story. I first heard this story from higher consciousness teacher, Caroline Myss, who, in turn, learned this first-hand from her friend and our protagonist, David Chethlahe Paladin. Conversation with the wonderful Lynda Paladin, our protagonist’s wife, added more meaningful background.

This is my favorite healing story. I first heard this story from higher consciousness teacher, Caroline Myss, who, in turn, learned this first-hand from her friend and our protagonist, David Chethlahe Paladin. Conversation with the wonderful Lynda Paladin, our protagonist’s wife, added more meaningful background.

David Chethlahe Paladin is a Navaho Indian living on a reservation in Arizona. David would laughingly say that his mother was a nun and his father was a priest. It turns out his mother became pregnant by a visiting priest. She, in turn, decides to become a nursing nun and leaves her son in the care of the extended family of their tribe.

David and his cousin spend a great deal of time leaving the reservation and going into town. They drink a lot, and they think life is better in the white man’s world. The local constabulary is forever returning the boys to the reservation. By the time David is 13 years of age, he is an alcoholic.

David and his cousin determine that they are going to make it off the reservation once and for all – and they do. They find their way to California, wherein they lie about their ages and sign up for work with the Merchant Marines. Here David befriends another young man from Germany. He also begins drawing; some of his sketches include the eventual bunkers that the Japanese are building on the atolls in the Pacific Ocean.

World War II is declared. The US Army tells David that since he lied about his age with the Merchant Marines he has a choice. He can go to jail for a year or enlist in the army. David enlists. He is a teenager.

The army tells David, as he is a Navaho, they are going to drop him behind enemy lines and use him as an information gatherer in their special services. Given his native language is a code that the Germans are unable to crack, much less decipher, David is to relay his findings to another Navaho who will translate and pass along the intelligence.

David is dropped behind enemy lines. Ultimately, he is captured and interrogated for information. The German officers find him useless and direct that he be sent to a death camp and executed as a spy.

Imagine, if you will, the scenes we all have invariably seen of the railroad station and the platform filled with lines of prisoners being pushed into box cars for transport to the camps. Here is David. He is being pushed and shoved into a boxcar. There is German soldier behind him saying “Schnell, schnell” (quick, quick). David stops, turns around and looks at the German soldier. It is his friend from the merchant ship. The friend recognizes David and ushers him to a different box car that will send David to Dachau.

In the barracks at Dachau, David sees an older man, a fellow prisoner, drop something. David bends down to retrieve it. The guard, who has witnessed this moment, asks David, “Are you the Christ?”

The guard then orders that David’s feet be nailed to the floor and that David stand there with his arms outstretched for three days like Christ on the cross. Every time David would falter and crumple the guards would hoist him up again. In the middle of the night, someone would sneak in and cram raw, maggot-covered chicken innards into David’s mouth.

When the Allies open up this camp, they find David a mere shell of a man, weighing maybe 70 pounds, and speaking Russian*. They turn David over to the Russians. David later speaks English and gives his name, rank and serial number to the Russians who transfer him to the US military.

David is sent to a VA hospital in Battle Creek Michigan where he spends the next 2 years in and out of a coma. At the end of two years, his legs are encased in metal braces, similar to what polio patients used. David, a young man, maybe not even 21 years of age, is to be sent to a VA home for the rest of his life.

David asks if he can visit his family on the reservation. The answer is, “Of course.” David literally drags himself onto the reservation. He meets with the elders of tribe. They ask to hear his whole story. David tells them every horrible thing that he endured. He is full of anger, rage, and hate.

The elders confer and tell David to meet them tomorrow at a designated point on the Little Colorado River. David agrees and at the appointed hour he arrives. One of the elders tethers a rope around his waist; others remove the braces from his legs. They hoist David up into the air and as they throw him into the raging current of the Little Colorado River, they say, “Chethlahe, call back your spirit or die. Call back your spirit or die.”

David would later say that those moments in the Little Colorado River were the very hardest of his life. He had to fight himself for himself. And he was able to see the big picture; he understood why things unfolded as they did. For example, he realized that the raw chicken parts were meant as a source of protein to sustain him so that he might live.

David Paladin was thrown into the river as a very shattered man. David emerged out of the Little Colorado River like the phoenix out of the ashes. He had metaphorically walked through the fire, or, in this case, swum through the currents, and had come out alive. He was born again.

And, that, dear ones, is what I think healing is all about for each of us. It is calling home our energy; it is calling home our disenfranchised pieces and parts. It is letting go of the toxic and the outdated. It is reclaiming ourselves.

David no longer needed his braces; he became a shaman, teacher, and artist and went on to work with priests and addicts. He died in his middle years in the mid 1980s.

* Remember David sketching during his tour of the Pacific and speaking Russian when the Allies first found him half-dead at the camp? It turns out that David was channeling, i.e., the Russian artist Kandinsky. In fact, Kandinsky’s best friend came for a visit to the U.S. from Russia. The friend, the story goes, told the press that he felt as he had spent the day with Kandinsky.